In other words, things just sort of happen in “Memoirs”. “Memoirs of a Geisha” is one quickly moving, impersonal scene after another: our sisters are sold into slavery scarcely before the credits are over, Sayuri moves from attendant servant to debutante geisha in a few training sequences (was I the only one who kept hearing “Team America”’s “Montage” song in my mind?), World War II is covered with a quick shot of some flying planes and a symbolic shot of red silk floating in a river, Sayuri regains her status before we even realize she has lost it. If I could pause for a moment, though, not to fully deconstruct the film’s messages-choice is better than no choice? love is better than prostitution?-but only to point out how very, very ambivalently they are embraced by the film itself, I might be able to account for the curious lack of emotional power with which the film passes over you. Apparently that tactic works with women as well, so yes, we feel the generic sympathy for Sayuri (and those like her) who are themselves sacrifices to the unattainable and often unarticulated dreams of others. Donaldson once wrote, is to give him something broken. The way to hurt a man who has nothing, Stephen R.

We understand, too, that having been born into a life with no education, money, or prospects, the only way of having anything is to accept one in which nothing is really hers. Oh, we understand well enough that she longs for a life of her own. We are not reminded of this prayer until the very end of the film, two hours (and it is a long two hours) later, when we are told-and we must be told, because we don’t necessarily see it-that everything in her entire life has been an answer to this prayer and that everything she has done, every step she has been taken, has been to bring her closer to this man. She wants to be a Geisha so that she can possibly see this man again and be a part of his world.

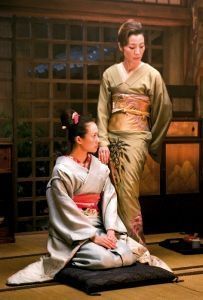

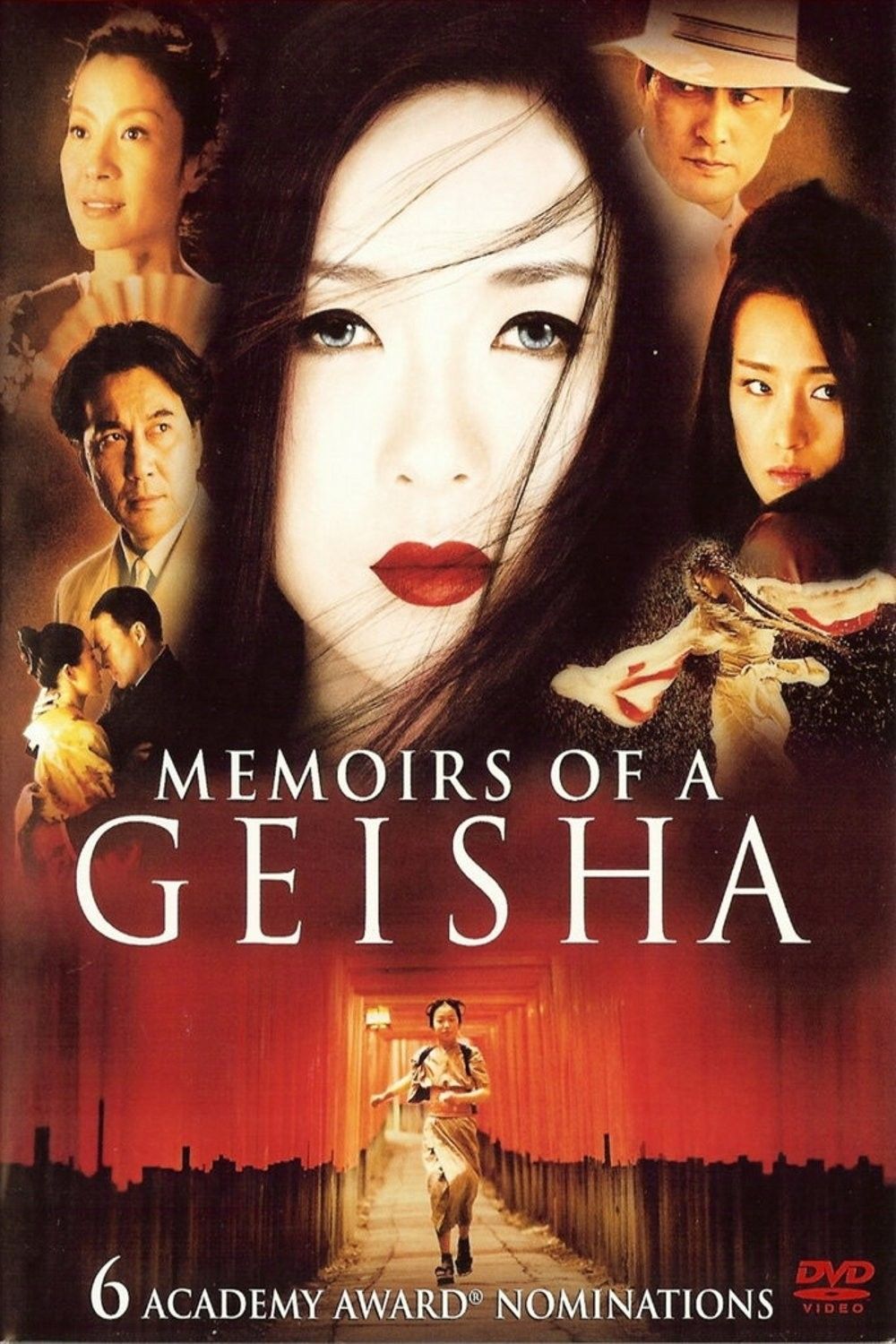

She takes the money she has received, more than she has ever had in her life, to the temple and sacrifices it as an offering to accompany her prayer. To this point in her life, Sayuri has been trying to either escape the house in which she has been sold or merely survive as a slave. I guess the key moment in “Memoirs of a Geisha”, from a Christian perspective, comes when the orphan Sayuri receives a kindness and a monetary gift from a then stranger on a bridge. It will no doubt garner praise for its technical artistry and sympathetic portrayal of gender oppression. The soundtrack, while overbearing at times, utilizes the skills of Itzhak Perlman on the violin and Yo-Yo Ma on the cello. “Memoirs of a Geisha” is a lushly shot, skillfully acted, and competently directed film. Although she has become the most famous and sought after geisha in her district, she cannot be with the Chairman ( Ken Watanabe), the man she really loves. Life is good for Sayuri, but World War II is about to disrupt the peace. After rigorous years of training, Chiyo becomes Sayuri, a geisha of incredible beauty and influence. There, she is forced into servitude, receiving nothing in return until the house’s ruling hierarchy determines if she is of high enough quality to service the clientele-men who visit and pay for conversation, dance and song. Plot: In the 1920s, 9-year-old orphan Chiyo ( Ziyi Zhang) gets sold to a geisha house. “A motion picture based on the novel by Arthur Golden, Memoirs of a Geisha” Columbia Pictures, a division of Sony Pictures

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)